Previous yearly reviews: 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2015.

This is my 10th year-in-review post – I just feel old writing that. Anyway, let’s talk about some themes of the year.

AI accelerates

Skip to the next section if you are tired of talk of AI; but for me, AI’s continued advancements remained the biggest topic. This was something that I experienced and felt first-hand. Early in the year, I dabbled in vibe-coding and did some small demos in office to spread awareness; at the time, professional programmers’ response was generally “this is cute, but not ready for real game-dev work.” (I was happy that they did start tinkering.) Fast forward to December, the most aggressive adopters’ mindset has already shifted to “I’m not writing any code anymore; how do I effectively manage many AI agents?”

It’s clearer than ever that we are in the beginning phases of an asymmetrical revolution to how all software (including games) is developed. Despite the current lack of mature tooling (and best practices / workflow know-how), we can already confidently predict that it will be far easier to scale AI agents than to hire and manage a large corp of developers. Each human programmer is now theoretically capable of performing as an engineering manager, managing a team of AI devs. And these AI devs will be working 24/7.

This revolution is and will continue to be controversial. Not all programmers want to be managers; many will continue to cherish handwriting code. Soft-skill attributes such as curiosity and bias for change will determine who survives (and thrives in) this turmoil. Quite possibly a lot of jobs will be gone. I’m not taking a moral stance here, but rather making a simple economics-based prediction: we won’t (and can’t, really) put the AI genie back into the bottle.1

Back to the practical implications. When I wrote “asymmetrical” earlier, what I meant is that many things that we previously considered as competitive advantages are going to be flipped upside down:

- The organizational capability to hire and manage large dev teams is a questionable asset now. Smaller teams have far less human communications (and alignment) overhead, and can drastically scale up production capacity with AI.

- Similarly, prior investments in optimizing human efficiency (in the old dev workflow) are also possibly rapidly depreciating in value. For example, game engine editor features / tooling that made it easier for manual editing (and enhanced productivity previously) could now be impediments to a full AI workflow (since they may be less AI-friendly to direct data manipulation).

It will still be years before the dust settles on the new software development paradigm; 2026 will be a busy year. At the same time, we are also seeing a brewing consumer backlash. I feel it’s partly a continuation of existing cultural wars (just a new battlefront), though this is clearly a tricky issue for developers to navigate. It’s also interesting how sentiment on this differs by country. There will likely be further conflict/drama before a realignment.

The market stagnates

Last year I spent some time sharing an analysis on the mobile games market. I was going to post updated macro charts (I already populated the data from Sensor Tower), but really the lines for market consolidation barely moved. Meanwhile, we have to put an even bigger caveat on not over-interpreting this data due to the growing fog of war: Apple and Google’s share of spending is rapidly decreasing thanks to factors like web-stores (DTC) and the Chinese mini-app platform.

With that said, let’s take a look at the top of the charts:

| Rank | 2024 | Revenue Growth % | 2025 | Revenue Growth % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MONOPOLY GO! | 93% | Last War: Survival | 36% |

| 2 | Honor of Kings | -9% | Whiteout Survival | 44% |

| 3 | Royal Match | 48% | Royal Match | -6% |

| 4 | Roblox | 20% | MONOPOLY GO! | -21% |

| 5 | Last War: Survival | 7535% | Honor of Kings | 5% |

| 6 | Candy Crush Saga | -7% | Candy Crush Saga | 0% |

| 7 | Whiteout Survival | 249% | Coin Master | 2% |

| 8 | Coin Master | -4% | Roblox | -42% |

| 9 | Dungeon Fighter Mobile | 3191% | Peacekeeper Elite | 9% |

| 10 | Peacekeeper Elite | -6% | Pokémon TCG Pocket | 137% |

- Illustrating the fog-of-war issue I just mentioned, Roblox mobile revenue did not decrease by 42%, but rather, they likely executed a successful shift to their own payment channels

- The Chinese 4x (or SLG, as Chinese devs would call them) games continued to scale up, all the way to the top of the charts

- 9 out of the 10 titles are the same, with the only change being Dungeon Fighter Mobile (its decline unsurprising, in hindsight) replaced by Pokemon TCG Pocket

The market continues to be difficult for games to break out. Scanning the top 100, we have the following 11 new entrants (as in, appearing in the top 100 for the first time):

- Gossip Harbor (no. 11) – an “old” game released mid-2022, but having a breakout year scaling up with 239% revenue growth, 137% downloads growth, and 198% DAU growth

- Kingshot (no. 15) – another Chinese 4x, globally released in 2025

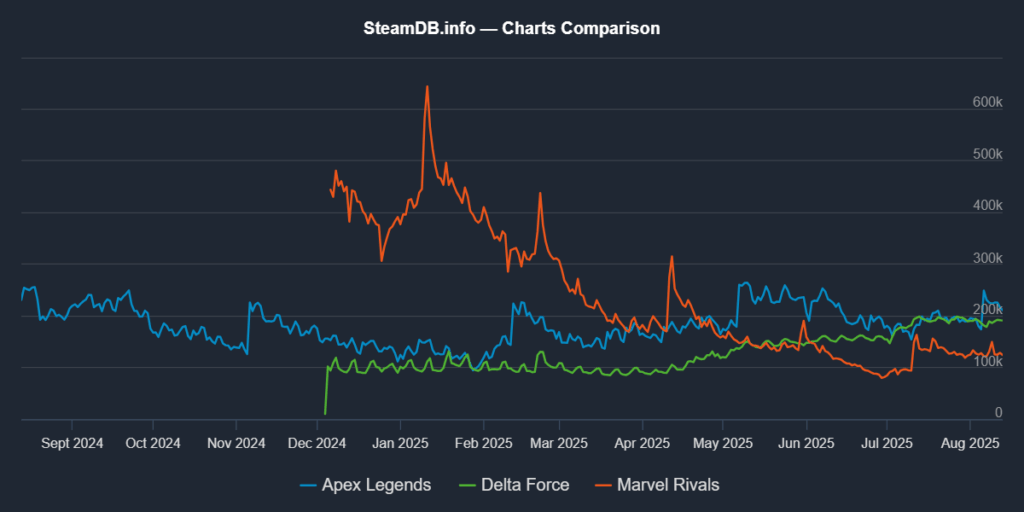

- Delta Force (no. 28), globally released in 2025

- Last Z: Survival Shooter (no. 29), globally released mid-2024, scaling up in 2025

- Royal Kingdom (no. 31) – globally released late 2024, so 2025 is its first full calendar year

- Dark War: Survival (no. 39) – guess the genre and which country this is from? Globally released mid 2024, revenue grew 840% in 2025

- Archero 2 (no. 67). Globally released Jan 2025

- Color Block Jam (no. 73). Globally released mid 2024, scaling up in 2025

- Disney Solitaire (no. 84). Globally released Apr 2025

- Seven Knights: Re:BIRTH (no. 87). Squad RPG, globally released Sep 2025

- Where Winds Meet (no. 94). Chinese MMORPG, globally released 2025

7 of the above 11 are from Chinese devs; 1 Korean; the rest are all casual genre from the west. Similar trend as last year.

A few other worthy callouts – not new entrants to the top 100, but impressive growth (>50% revenue growth) in 2025:

- Clash Royale (no. 13, 152%)

- TopHeroes (no. 41, 135%)

- Seaside Escape: Merge & Story (no. 49, 67%)

- Wuthering Waves (no. 56, 56%)

- CookieRun: Kingdom (no. 82, 83%)

Game devs, what is your China strategy?

(This could have been its own post, but I got lazy.) With the increasing dominance of Chinese devs, it’s worth being a bit provocative towards game devs elsewhere: do you have a China strategy, from the following perspectives?

- China as a market opportunity – is this something you care about? I’m very opinionated here. On mobile, I remain bearish for the “average” foreign studio. The regulatory barriers to entry remain very high (only 95 licenses granted to foreign games in 2025, compared to 1,676 domestic), while the home turf competition is astronomical. It’s a hugely lucrative market for the winners, but it’s arguably not even worth the effort for the rest. Steam is a whole other story, but we should remain vigilant about the continued legal uncertainty

- Chinese talent. Chinese devs have accumulated strong know-how in specific genres and mobile. Is this capability of relevance to you? If yes – unlocking it is not straightforward (build/buy/partner?), but perhaps worth a deeper investigation.

- Chinese games going global – from a defensive perspective, how are you stopping them from taking your lunch? Or stated neutrally, what do we think the stable equilibrium will be of Chinese games’ market share in western markets? Will this play out more like the film industry (where Hollywood productions collectively dominate the box office everywhere, aside from a few specific markets), or the auto industry (with a lot more geo-market share variance, associated with regulatory protections)? A common critique I hear is that Chinese devs still don’t have the cultural taste for the west – how strong is your conviction that they will never acquire this (or, can they acquire it faster than you can catch up in capacity deficits elsewhere)?

Personal bits

I didn’t play a lot of new games in 2025. I remember spending a lot of time on Hades II while it was still in early access, but ironically I still haven’t experienced the ending since its 1.0 release. In December I jumped on the extraction shooter train, but no, not Tarkov or Arc Raiders, but rather Escape from Duckov, the PC game made by a tiny Chinese team. It is very good, especially the first 20 hours. It’s clear the devs took to heart key design principles from not only Tarkov, but also games like Dark Souls and Diablo, and fused them together in a truly addictive package with a whimsical (and smart – as in cheap to produce) art style. And on mobile, more than anything I played a lot of Merge Tactics in Clash Royale. (It’s great to see the former Clash Mini team take another swing at mobile auto-chess.)

During the summer I started binging The Expanse. First the TV series, then the books – all of them. One thing that left a strong impression was how I felt the writing noticeably improved after the first book. Perhaps it’s just a subjective feeling, or, this is a good example of craft growth.

I kept up decent active habits (for my standard), averaging 10,882 steps per day which was a small 2.5% increase over 2024 (10,608). I kept up sports climbing, continuing at a fairly beginner level but somehow managing to sustain some over-use injury on my fingers (so I’m taking a few weeks rest currently).

- I’m not endorsing a laissez-faire position either: sensible (consumer-oriented) regulation of AI is needed, similar to how there is growing appreciation for regulating social media. ↩